Pioneer Days

Okay… what was happening in the outlying towns?

The surrounding white settlements, based on and around farms, mines and trading stores were effectively depopulated by March 25, the residents either being killed or seeking refuge in the three "urban centers" (we'll talk about Mangwe later). The Matabele hemmed in the smaller centers of Gwelo and Belingwe which, as Cobbing (1976: 400) says, "became, without relief, impotent". Gwelo, in contact with Bulawayo by telegraph (which the Matabele only cut on April 1, a sign of increasing tactical sophistication) knew of the start of the war on March 25 when urgent messages about the encirclement of Bulawayo were transmitted almost at the same time that Ronald Napier rode into town from Shangani full of knowledge about the killings. The town went into laager at 2300, although they were ill-prepared any attack; only 40 rifles and 2000 rounds of ammunition were rustled up. Gwelo screamed for help. Captain Gibbs was immediately despatched from Salisbury at the head of 12 men but carrying two Maxim guns, 50 rifles and 21,000 rounds of ammunition in a coach. They were in Gwelo by March 29 and found that 350 men, 27 women and 22 children had taken refuge in the rough laager. Gibbs formed the Gwelo Volunteers with 284 men a week after the laager was fortified to his satisfaction. Like his Bulawayan counterparts, Gibbs launched patrols into the surrounding countryside, and was beaten back by the Matabele. The men from the Amaveni impi fired upon the first patrol on March 30 and two days later attacked Gibbs's "friendly" Shangaans, who were nothing more than mine laborers, killing 20. Gibbs counter-attacked but was forced into retreat and finally, to remain into laager after April 22.

Was Gwelo's laager any different to Bulawayo?

Information from Mrs A. Hurrell: Looking towards the western side of the Gwelo laager from the parade ground, July 1896. Left to right: Cecil Rhodes's wagonettes; the officer's mess; Percy Brown's office; Sergeant's married quarters; Guy Hurrell at left centre; Mrs Hurrell's dog at centre.

Gwelo's laager was situated at the corner of Lobengula Street and 5th Avenue – where the main police station is today. A well, now filled in, was located at the north-west corner of this crossroads that may have been used. Unlike in Bulawayo, it was decided to sacrifice the buildings around the area of the laager to give a better field of fire. Falk (1970: 10) evocatively writes, “as Gwelo was not a large village, this reduced the houses to quite one half. They were mostly pole and dagga... so a few fatigue parties soon demolished them, but the burning of these houses gave the natives courage, as we afterward heard them saying we must be afraid of them to pull down our own houses”. The laager was rebuilt by Gibbs in a triangular shape instead of the usual square (Richards 1974: 102). Falk gives an idea of the different mentality in the laager once the initial fright had passed: “The funerals during laager were many, not from wounds, but fever and dysentery, and were very sad... Life was very monotonous, a scare now and then at night [from accidental shots]... and as all lights were ordered off at 9 p.m. I can assure you it was anything but lively. Gambling was carried to excess by the men [cards sold for £2 a pack]... everything was painfully expensive”.

And in Belingwe?

Belingwe store and laager.

Sandawana's home saw a great deal of action in 1896. Named for the nearby mountain of ku-Berengwa (which means distinguished – of course), this hamlet only received news of the uprising on March 26 when a runner brought a letter from the Insiza NC, Fynn, who reported the murder of the Cunningham family and a mine manager nearby. Messages were sent to all the people in the surrounding district to congregate at the store, and as Laing recounts, "through the timely warning… most of the men in Belingwe were banded together and in a position to protect themselves and public property in less than twenty-four hours". Tyrie Laing, in command of this enlarged settlement, was content to employ a passive approach, the only forays consisting of sending messengers to Fort Victoria and Bulawayo for news, supplies and assistance. His passivity encouraged the Dumbuseya, Rozvi and Lemba of the area to attack the white's cattle laager on April 12, where they emerged with almost 200 head, half the total. From prisoners, Laing learned that the plan for that area was to wait for reinforcements from the Godhlwayo-led Matabele before attacking the Belingwe garrison and moving on to ally with Nhema's Mhari near Fort Victoria. Belingwe's precarious position was mildly assuaged by the hostility displayed by the locals towards the Matabele and by the neutrality of the majority of the Ngowa to the south but Laing was determined to wait for reinforcements before launching any offensive actions. After all he only had 44 white soldiers, one white woman, 10 “Cape Boys” (black soldiers from the Cape area) and 15 “Zambezi Boys” (BaTonga) who looked after the cattle.

What was the laager like?

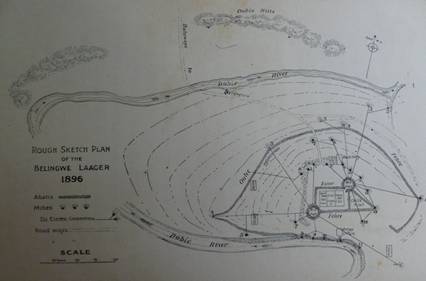

Laing's 1897 map of the laager at Belingwe. Today only a small portion of the lower fort (Fort No. 2) survives.

Our best source is Laing's (1897) book where he describes the defenses as consisting of two redoubts, built in a couple of days, thanks to a gang of blacks working as impressed labour. Sentries were mounted on a full-time basis and as in Bulawayo, a set of dynamite mines were dug in around the centre of the defenses. Unlike many other garrisons, Belingwe had ample food supplies and the men constructed a series of water storage tanks. As was common, they did not come from the war unscathed since accidents with firearms and fever took their toll.

How did the whites break out of Bulawayo?

First let's talk about the disposition of Matabele forces by this time. They had consolidated their positions along the middle Khami River to the north-west, and had taken over the upper Umgusa Valley, thus practically encircling the town. As Cobbing (1976: 403) reveals, we can't be sure of who was where but good guesses can be made. Nyamanda and Mayeza were in control of an unknown number of soldiers on the Khami River, and leaders on the Umgusa included Galu from Iliba, Ntabeni from Babamba and Sikukulwana from Induba collectively commanding about 10,000 (Blake 1977). Ransford (1968: 94) argues that "technically it was not really a siege, but rather an investment since the rebels never entirely surrounded the town; they left open the vital road to Mangwe and Tati". (Some semantics: an "investment" is an archaic term referring to the surrounding of a place by a hostile force in order to besiege or blockade it while a siege is more properly defined as when enemy forces surround a town or building, cutting off essential supplies, with the aim of forcing the surrender of those inside.)

Sourced from the Zanj Financial Network 'Zfn', Harare, Zimbabwe, email briefing dated 28 March 2011

South Devon Sound Radio

South Devon Sound Radio Museum of hp Calculators

Museum of hp Calculators Apollo Flight Journal

Apollo Flight Journal Apollo Lunar Surface Journal

Apollo Lunar Surface Journal Cloudy Nights Classic Telescopes

Cloudy Nights Classic Telescopes The Savanna - Saffer Shops in London

The Savanna - Saffer Shops in London Linux Mint

Linux Mint Movement for Democratic Change

Movement for Democratic Change